I enjoyed this blog post from editor John McIntyre. In it, McIntryre writes,

[T]here are no certainties, only judgments.

Of course English grammar has rules, scads of them. Even non-standard constructions like ‘Me and Madison are going to the mall’ follow observable grammatical principles. But the rules are complicated, with subtle variances and many exceptions. It requires judgment to apply them aptly on particular occasions.

….

If you are an editor like me, you ply your little coracle amid the swells of language. You have your own tastes, formed by years of wide and thoughtful reading. You have the examples of the best writers you see currently published. You have authorities, like Garner, Butterfield, and MWDEU, whose disparate views and advice you sift. You have a sense of the varying registers of English and of which may be most suitable for your author, your subject, your occasion, your publication, and—most important—your reader. You have a memory of your past judgments and how they turned out for good or ill. These are the tools of your navigation.

What you do not have is certainty.

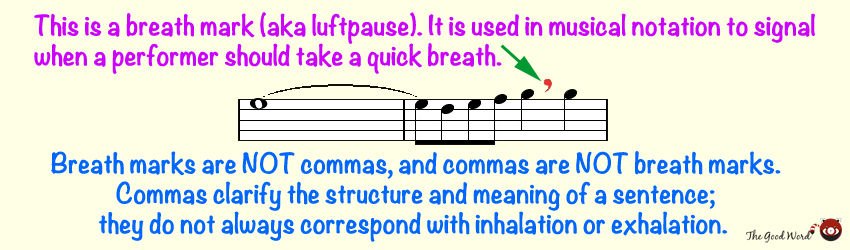

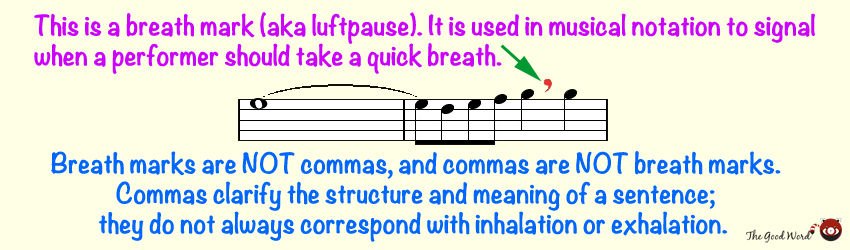

In addition to admitting that I had to look up the definition of “coracle,” I’d only emphasize that McIntyre does suggest that judgments about grammatical norms must be applied aptly, which I might coax and twist ever so gently to argue that those judgments should be based on a logical rationale; that is, the reason for applying a particular convention of grammar or usage should be more than just intuition or how it sounds. (Don’t even get me started on teachers and tutors who tell students to just place a comma wherever they’d take a pause for breath when reading aloud; that is unreliable and sometimes outright incorrect advice!).

Those rationales often come from the authors of the language-usage resources that McIntyre mentions, and I sometimes also refer to scholarly journals, websites, and books about linguistics and the history of the English language. To provide accurate reasons for why a specific grammatical or stylistic convention applies, we have to constantly research the latest trends in proper usage because style guides get revised and conventions change. Moreover, even experts can be wrong about minutiae. For example, for the longest time, I thought United States was abbreviated as U.S. in MLA style. However, when a savvy student of mine from years ago used US throughout one of her essays, I decided to double-check, and sure enough, she was correct, and I had to change that particular habit in my writing and in marking papers. It seems like such a trivial matter, I know, but this kind of required research underscores that diligent teachers, editors, and writers of all ages are constantly verifying and updating their knowledge of preferred conventions because depending solely on one’s memory can lead to errors.

This is why I tend to side-eye grammar advice that’s based on something someone read or was taught—or possibly misread or misremembered—from 5, 10, or 50 years ago. I often see people write in comments, “That’s what Mrs. So and So taught me in third grade, and I’ve gone by it ever since!” It takes extra time, but looking up the latest guidelines can be eye opening, even for seasoned editors, instructors, and authors.

By the way, I can tell you that when a writing professor/coach + academic editor who loves descriptive grammar (me) marries a linguist + academic and book editor with the same obsession (the hubby), you spend a lot of time talking or arguing about syntax and usage, and terms like “restrictive” and “fricative” get thrown around a lot (and there is nothing kinky about that, thanks!). We usually agree, but not always. No objects get thrown, mind you; this isn’t Dynasty for language nuts or anything. However, if someone wants to produce a show in which teachers, editors, and other word nerds throw down, MMA style, over grammar with, say, Stephen Pinker and Stephen Fry officiating and Michael “Let’s Get Ready to Ruuuuumble” Buffer announcing, I would totes watch that.